Whose Name Should Be on Ghostwritten Blog Posts?

When you're paying someone to write blog posts for you – the process known as ghostwriting – you have one crucial decision to make. What name do you assign as the author for the post? There are a lot of possible options, all with their own pros and cons. Let's take a look.

Who Owns Ghostwritten Content?

First, we should clear the air about one thing, and that's about the ownership of content. With ghostwriting, there's a question of who owns the content. One person wrote it, another person publishes it with their name (or another name) on it. Who owns it?

The answer to this question comes down to contracts.

By default, if no contract is signed or otherwise made and honored, the content is owned by whoever produced it initially. At the most basic level, the moment the content is created (and it is sufficiently unique as to not be considered plagiarized or a violation of copyright in another way), the copyright for that content is considered to be owned by the person who wrote it. That means the ghostwriter owns the content.

Luckily for you as a business, this isn't true as soon as a contract gets involved. Whether you're buying content through a content mill, from a freelancer on a portal site, or directly from them via their own website, you want to have a contract. The decision of which to choose is up to you.

With content mills, the contract is part of the mill itself. By creating an account and paying for content through their website, you're agreeing to the contract. By registering an account and producing content, the writer is agreeing to the contract. It's part of doing business on the mill itself.

With individual freelancers, particularly if you're contacting them on your own, you'll want to have a contract written up and signed by both parties. The writer might have a standard contract they use for all their business, or they might be used to signing any contract that comes their way.

Thankfully, a contract doesn't have to be complex. All it needs is a clause stipulating that the writer will uphold their end of the deal, an clause stipulating that the business will uphold their end and pay for the content, and a clause about passing rights to the content over to the business. The ghostwriter essentially gives up their claims to the content when you buy it, and you own it as if you had produced it.

This gets a little more complex when you consider that there are different levels of rights a writer can sell or sign over. With ghostwriting this is relatively simple, but with other forms of media it can get quite complex. Look up things like first broadcast rights, international publication rights, right of first sale, and so on. As it turns out, intellectual property rights are super complex! That's why lawyers specialize in it as a field, or even in specific subsections of the field, like copyright law or patent law.

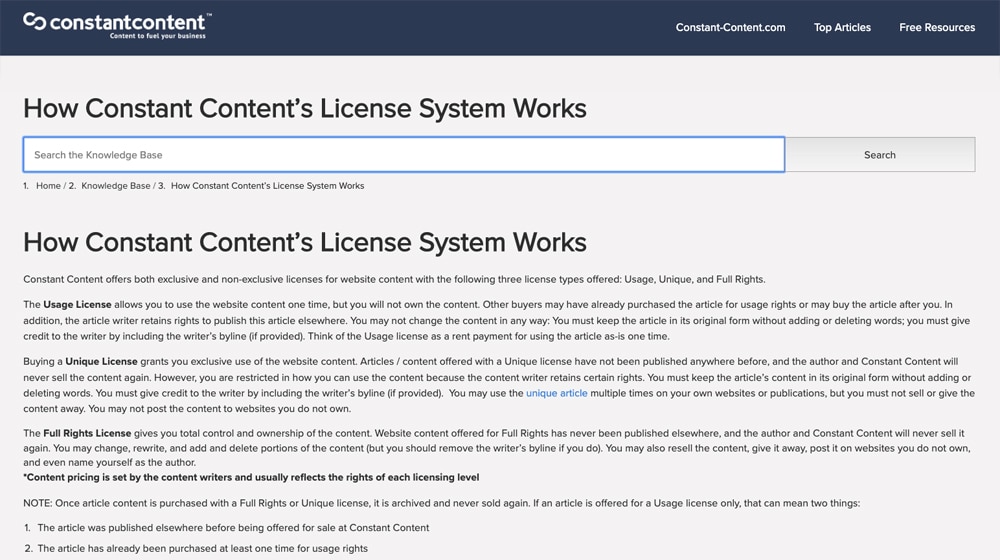

Constant Content is a content mill that has a rights system with some flexibility. It's not really widely valuable these days because of some Google changes from back in 2011, but years and years ago, it was useful to both writers and buyers. They specified three levels of rights, to give you an example of the kinds of rights you can buy.

- Usage Rights. This is the weakest level of rights. You buy the ability to use the content, as-is with no modifications, and with credit to the writer. You don't own the content; you only purchased rights to use it. This is similar to how you can license a stock photo, but so can other people.

- Unique Rights. This is a mid-tier level of rights where you buy rights to the content and can use it, but you cannot edit it. The writer still maintains certain rights, and you have to give credit to the writer.

- Fill Rights. This is the high tier of rights and is what most content mills and ghostwriting contracts will give you. You buy the full rights to the content and own it afterwards. You don't need to credit the writer, and you can edit the content if you desire.

Among these, usage rights were typically have the price of full rights. Paying less for content means you could get it cheap, but you might not be the only person publishing it. This wasn't a problem in the pre-2011 days, but once Google Panda started penalizing duplicate content, usage of this rights level dropped off dramatically.

Full Rights is typically what ghostwriting is all about, and it's what most ghostwriters expect. It's only when you hire a writer on to write under their own name that you have to consider ownership in a different light.

So why does your choice of attribution matter? I can think of three main reasons.

Google gives preference to content with a high EAT score. The EAT score is Expertise, Authority, and Trustworthiness. This is a way they are using machine learning to develop expertise portfolios for the people who have content attributed to them, among other things. If there's no listed author, a generic author name, or what have you, there's no one to call an expert, so there's no expertise.

Users tend to trust content more when there's a name attached to it that they can recognize. If you see a blog post on a site you've never heard of before, and it's written by Rand Fishkin, you already know that it's going to be a good post with good insights, because you recognize Rand's name. If the name attached to it isn't someone you recognize, you can look them up and see what else they've written. You want that name recognition under your control.

Content attribution becomes a portfolio for the person attributed. If you're attributing your content to the name of the ghostwriter, and that ghostwriter goes on to disavow your company, or they stop working for you and move on to other things, you have a whole lot of content acting as a portfolio for someone who no longer benefits you. If you attribute it to the CEO instead, your CEO gets to reap those benefits as a thought leader in your industry, though they still take that reputation with them if they leave.

So what are the various options you have for bylines for your content, and what are the pros and cons of each?

Option 0: No Attribution

The first option used to be a lot more common, but is becoming increasingly less common as the years go by. That is, not attributing the content at all. It's on your site, so its yours, attached to your brand, and that's that. No author, no attribution, no byline, just content living on its own.

There's not really much benefit to this unless you're paranoid about high turnover rate amongst your employees and contractors. I've seen some companies even include a clause in their contracts that, if a writer leaves or severs their relationship with the company, the company can reverse attribution of their content. Still, it's not a good option when it's so trivially easy to add any attribution whatsoever to your posts.

Option 1: Admin/Team Name

A second option that I see somewhat frequently even today is attribution to the company or the team. There's still an author line and it's filled out, but it's not filled out with something that's really important. So you might see a blog post published by "The Content Powered Team" or by "Admin" or something of the sort.

This has the benefit of having some level of attribution, and it does allow you to create several sub-teams within your organization. A company like HubSpot, that runs several large blogs with interrelated content, could publish content under names like The Marketing Team, The Outbound Team, and so on. It keeps a unified front while still giving attribution to teams.

Unfortunately, this is still zero name recognition or portfolio building for anyone. You lose some of the Google EAT score, and it's not useful for a user who might want to look up an author to see what else they've written.

The "admin" option specifically is also bad because it's the default WordPress gives you when you create a new site. This indicates that you haven't changed things in your WordPress configuration, which means there may be security holes or exploits a hacker could use to compromise your site. It's a minor thing, but it makes life easier for anyone attacking your business, and that's never a good thing.

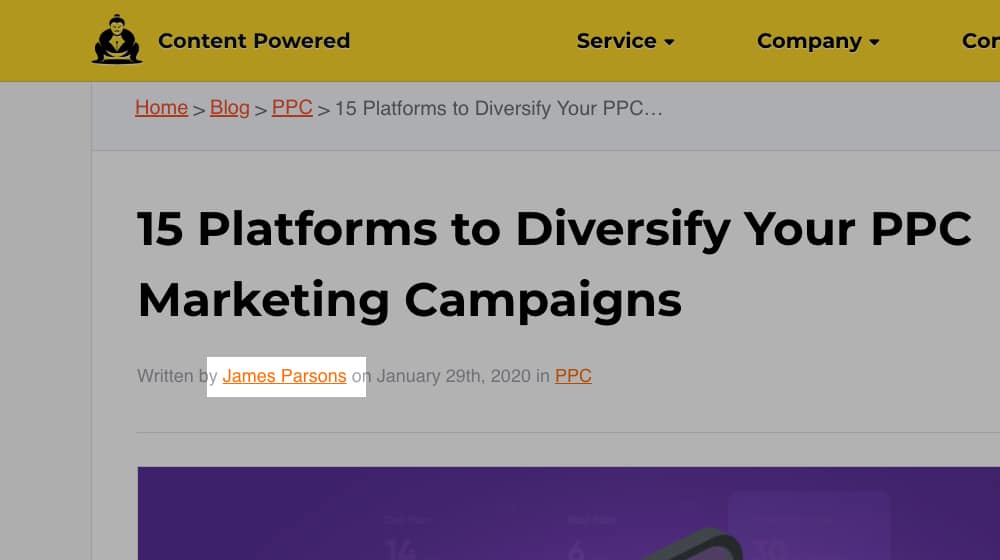

Option 2: CEO's Name

Attributing content to your CEO is one of the more common options I've seen among small and medium businesses. You get it a lot when the CEO is also an entrepreneur, and they may also be creating new businesses from time to time. Neil Patel is a prime example of this; he attributes content he pays to have ghostwritten to himself, and uses that position of thought leadership to position himself favorably when creating new businesses and new relationships.

That's not to say that the attributed CEO is doing nothing. I have no doubt that Neil Patel knows his stuff, and he – and many others in similar positions – at least tend to be the ones to give the ghostwriter the ideas, direction, and even sometimes rough drafts. It's just that a CEO doesn't always have time to be doing the manual labor of creating those posts when they could be spending their time making a ton of money in other ways instead.

The downside to this is that a lot of casual readers might not believe that the CEO is actually the one doing the writing. It kind of breaks the kayfabe inherent in blogging. It's rare that the "shocking revelation" of a blogger ghostwriting their content is somehow damaging to them, but there's a certain level of plausibility.

After all, no one really expects Robert Iger, CEO of Disney, to be the one actually writing blog posts for a Disney blog. CEOs do occasionally step in and write high-impact content, but it's typically treated as a big deal, not as a causal daily blog column.

Option 3: Blog Manager's Name

A lot of times, with mid-sized businesses where the CEO is off doing their own thing, managing a blog comes down to a blog manager. In the absence of other direction, often times the blog manager becomes the public face of the company for their blog. They have the name attached to the blog posts.

This isn't a bad thing; the blog manager is doing a lot of work to manage the blog. They're developing the content plan, they're finding the ghostwriters to produce the content and working with them to deliver topics, ideas, and quotes that get turned into the finished product. Many blog managers also do actually do some writing for the blog, to fill in spots or to contribute when they have the time.

The only downside to this option is the same as with other options where everything is attributed to one person. If that one person leaves, they take that thought leadership with them, and you generally have to attribute new content to someone else. You can't keep using their likeness when they aren't part of your organization anymore. If your blog publishes multiple posts a day, as well, it can be implausible that one person produces that much content and again breaks the kayfabe.

Option 4: Writer's Name

In some cases, you might have a team of writers for your blog who write part time, and who have ghostwriters fill in the rest of the time. This is usually the case when your writers are employees who have other jobs to do, but lend their likenesses to the blog and write the occasional post.

You get diversity of author bios here, so it looks like your business has a number of good writers working for it, and the ghostwriting fits in. On the other hand, you do run into issues with who gets what content attributed to them, and it can be a bit of a bookkeeping mess. Still, it's perfectly plausible.

Option 5: Ghostwriter's Name

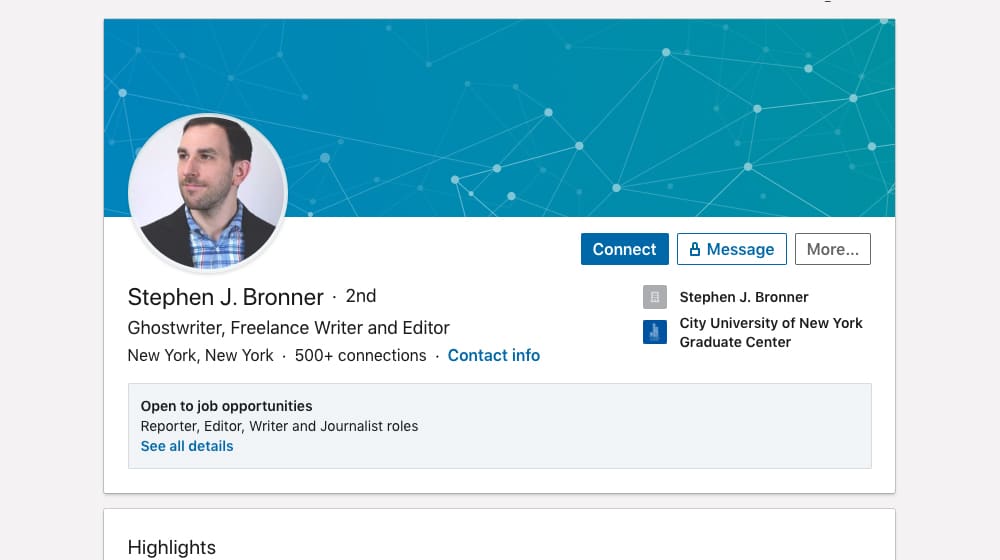

Sometimes you can consider converting a ghostwriter into an actual writer. Ghostwriters often want to build up their own portfolios, but may not know how to do so, or may be spending so much of their time writing for pay that they don't have energy left to write personal development pieces.

Typically if you're going to attribute your content to the actual ghostwriter, they're no longer a ghostwriter. You usually want to hire them on as an actual employee, or otherwise adjust the terms of the contract to reflect that you're publishing under their name sometimes. This is, also, only a good move if you have a good relationship with the ghostwriter.

Option 6: Fake Persona

Here's an interesting option for you. What if you just… made up someone, and used them as your author?

This has a few benefits. For one thing, they're never going to betray you, leave the company, or interfere with your blog in some way. They can't disavow you because they are you. They're also pretty easy to set up. All you need is a name, really. You don't even have to worry about trying to find a stock photo model to use their likeness and having it be discovered – you can use an AI-generated photo from a site like this.

On the other hand, you might run into issues if your persona starts to move up in the world. What do you do if someone approaches them looking to hire them from under you? What if they're invited to a speaking engagement? You don't want to reveal that they're fake, but at the same time, you don't want to turn down opportunities like those.

I don't have an answer for you there. You just have to make the decision if it comes down to it.

Which Should You Choose?

At the end of the day, most of these options work fine. As long as you have some kind of attribution for the content you purchase and post, you're getting most of the benefits you want out of it. Everything else is just gravy. Personally, I recommend the CEO option for small businesses, and the blog manager or writer options for larger businesses. Really, though, just have some name on it and you'll be fine.

August 27, 2020

I'm a part-time ghostwriter and my client uses his name as the author of the posts, and he's the CEO of the company. Whether he wrote the content or not, since he is the representative of the business and paid for the rights to the content, it's his right to use his name. If the company bought the content already, this is already considered as the company's property. Good to get a second opinion on this though, I always find it funny when ghostwriters get upset when they can't put their name on their content... that is literally the opposite of a ghostwriter!

August 30, 2020

That is funny! You definitely have to understand what being a ghostwriter entails before you take on a client; once you finish writing those articles you are no longer the owner of them and they belong to the company that paid you. Thankfully I haven't ran into this issue yet, but it may just be a general mis-understanding of what ghostwriters are in general. Thank you for sharing your experience

April 29, 2021

My new writer wanted his name to be published on my articles.... but I'm the one paying for them, and I'm trying to build my personal brand. I didn't know if I was taking crazy pills or if I just didn't understand how this process works. Thanks for helping me clear that up.

April 29, 2021

Hey Colby!

No problem. The truth is, there's no right answer. It depends on your agreement between you and the writer.

If you have a writing staff who you employ full time, it makes more sense for articles to be published under their individual names.

If you're paying for a freelancer to write articles for you, it makes less sense to publish them under their name.

June 16, 2021

I don't understand why there are ghostwriters who want their names on the article. Isn't it obvious that they are called "ghostwriter" for a reason?

June 17, 2021

Hey Daniel! You're preaching to the choir 🙂

July 21, 2021

My writer is trying to tell me that he wants to be listed on the article name instead of my name. What do I tell him?

July 24, 2021

Hi Kevin!

There should be an understanding between you and the writer upon hiring.

Hopefully, you can communicate that to them. You own the rights to the content that you purchased.

If it doesn't work out with this writer, you can chalk it up to a lesson learned. Make sure this is communicated to new writers in the future before hiring.

Good luck!

October 06, 2022

I had the same dilemma. I assumed my writer knew what being a ghostwriter entails but he didn't and that was on me for not setting the terms more clearly.

October 07, 2022

Oh man. Hopefully you got that sorted out!

January 09, 2022

As a ghostwriter myself, I think it's pretty clear to not expect our own names on articles we ghostwrite. But I guess it wouldn't hurt to always make that clear before hiring since some may be new to this idea.

January 12, 2022

Hey Steven!

I've had both writers and client ask me this. It never hurts to make it more clear, for sure!

April 12, 2023

I miss the lazy days when I could just attribute content to fake personas and create websites that looked a lot larger and "more important" than they really were. Today, people will try to find who the person is (especially if they like the content and desire to follow the author on social media). When they find nothing but the posts on your own sites they will assume it is a fake person and stop reading.

April 13, 2023

Hey Carol!

I agree. But then again, it's easy to fake social media pages, too.

It's an interesting problem. Large publishers are facing this, too, especially when there is an incentive to own author accounts on those sites. Marketing agencies call them "pseudos"; fake users with fake photos and fake websites / social media accounts. They are created solely for marketing purposes and do not exist.

At a certain point, it's so hard to tell who's real and who isn't. Search engines lean on many signals for their EAT algorithm, but those aren't perfect, either. It's disturbing how possible it is to create new fictional identities like this.